Like any good game, Super Metroid contains plenty of secrets. Some intentional, some less so. The sheer number of working parts in the game that collide as you put the programming code through permutations the developers couldn’t have predicted or accounted for inevitably make for some surprising interactions.

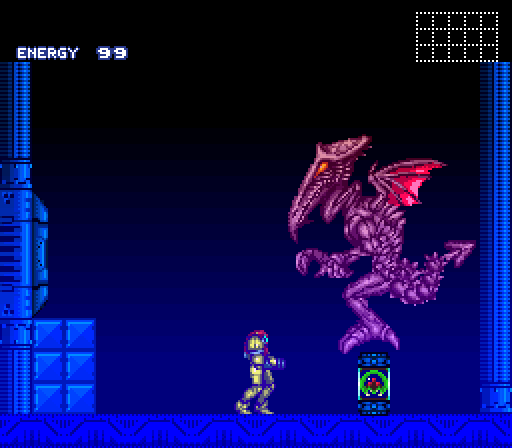

Some of the details are simply there for fun. If you manage to best Ridley in the prologue, it doesn’t change the outcome of the game… but it does embarrass your enemy by causing him to lose his grip on the baby metroid’s container. Rather than flying off because you’ve been bested, he takes off because you’re too awesome for him to deal with while he has to worry about his captive.

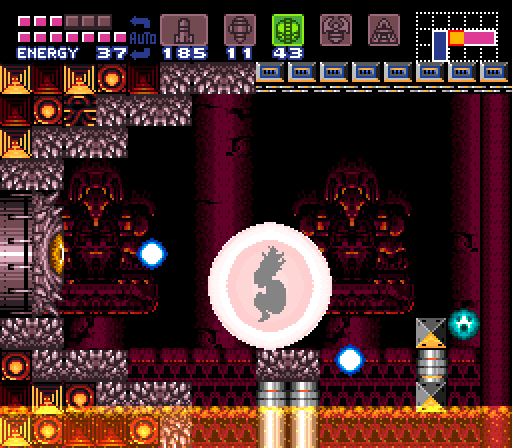

But then there are more arcane secrets. The Crystal Flash technique is demonstrated in the game’s rolling attract mode (which I didn’t even realize existed until I saw it on a demo loop at Waldensoft), but the attract mode doesn’t tell you how to activate it.

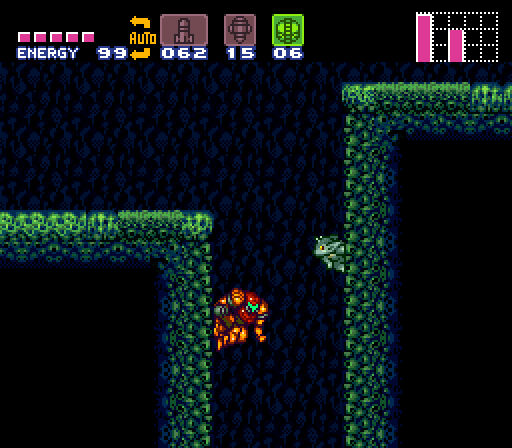

Besides being a Michigan-based chain of gas stations, Crystal Flash is also a super technique that allows Samus to convert weapon energy into health when low on life. The conditions for activating the ability are terribly specific: She needs to have 50 or fewer points of health, a large stock of all expendable weapon types, and nothing in her reserve tanks. Pressing an arcane button combination while in morph ball form will then allow her to enter this sort of energy cocoon that drains her weapon stock in order to restore health. It’s cool-looking – one of the few times we see Samus without her Power Suit outside of the original Metroid‘s New Game + – but few people would ever discover it on their own. It’s there, though, just in case.

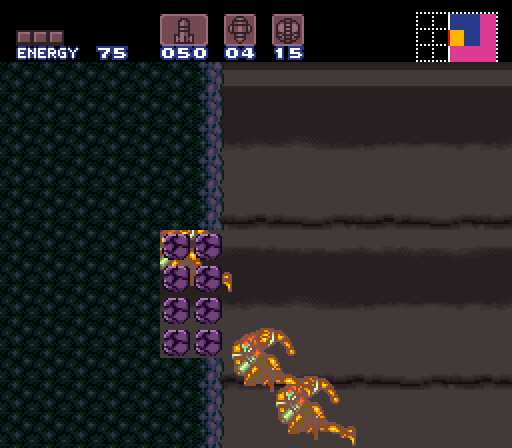

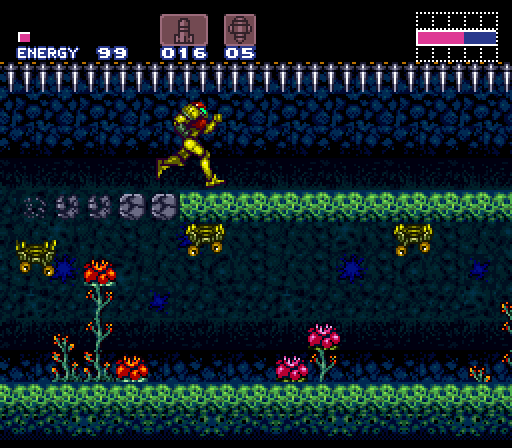

That so many details were accounted for actually is one of the game’s more surprising features. The wall jump, for example, is a hidden ability that requires practice to master. And while you can use it to acquire certain items out of order, locations where you might potentially put it to use to severely break the game’s intended sequence have almost entirely been accounted for. Likewise potential bomb jumping sequence breaks; rather than removing a feature that allowed players to break open the original Metroid, Super Metroid‘s creators left it intact without gimping it and simply built their stages to reflect their awareness that their fans would be experimenting with that technique. This is the definition of great design: Empowering players, never tying them down or stripping away their abilities, but taking great care to make sure that empowerment doesn’t diminish the game experience.

Of course, there’s no stopping a truly determined army of obsessed fans, so naturally Super Metroid players have found weak points in the level layouts, or other ways to exploit the game design.

For example, even after you learn you can perform the Shine Spark flying dash, you may not realize you can execute it in several different directions. Up is obvious, but you can also fly along flat surfaces. If you’re really good, though, you can fly at a 45-degree angle – this requires exquisite timing and has very few practical applications. But you can use it break through a secret wall in your gunship’s landing area to access a small set of rooms that you could normally only reach upon returning from the Wrecked Ship through a certain door. There’s no real advantage to doing this, but again, the sense of personal empowerment that comes from doing things the “wrong” way is undeniably satisfying.

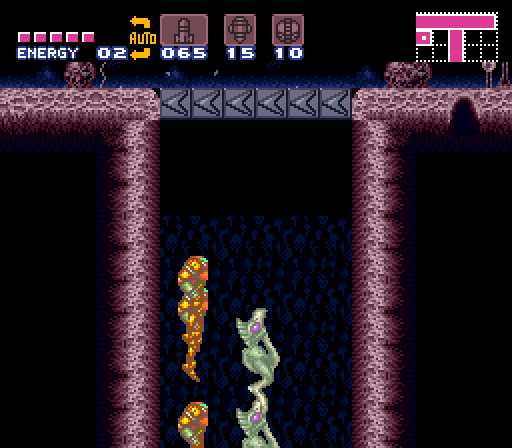

I’ve mentioned a few areas where the wall jump can be used to get to certain items out of proper sequence, but even here in the tutorial area you can find a test of wall jumping skill that goes beyond merely mastering the timing of the action. There’s a narrow gap in the wall to the right at the top of this shaft, only one block high, that Samus can’t simply leap into. Once she has the Spring Ball, it’s a simple matter to hop over there and acquire the power-up within – but you’re likely to stumble into this section long before acquiring that tool. With truly spectacular timing, though, you can wall jump over to the right and duck quickly into a ball, collecting the power-up and saving yourself the trouble of returning to pick it up later. Again, this is totally inessential… but when you pull it off, it feels amazing.

There are even more advanced exploits, things so specific and unintuitive the developers clearly never thought to test for them. For instance, you encounter a number of collapsing floors and descending gates early in the game that you should only be able to clear once you have the Speed Booster. But if you do an unaccelerated run while toggling the 45-degree aim controls, the resulting animation glitch may allow you to clear the descending gates before you’re supposed to. This can result in a more extreme form of sequence-breaking than simply snagging an extra missile early; one of the items hidden behind these gates is the Ice Beam, which allows you to gain access to all sorts of interesting places. Likewise, it’s possible to open green missile gates from the wrong side, granting you the ability to poke around in areas that you should only be able to explore much later in the game.

These tricks and exploits lack the enormity of, say, the “minus world” in Super Mario Bros. or wall-walking in the original Metroid. Nevertheless, they’re a part of the game, and they’re grown over time to be a part of its fan culture. In a sign of class, the Metroid folks acknowledged Shine Spark exploits in Metroid Fusion, locking down certain potential sequence breaks but at the same time acknowledging the skill required to pull it off. That sure beats Retro’s approach to the double-jump exploit in Metroid Prime, which they simply ironed out of the game altogether in rereleases of the game. Where’s the fun in that?

Both with and without its secrets and exploits, though, Super Metroid stands as a true classic. Its intuitive, gamer-friendly design walks a delicate tightrope between developer control and player freedom, and even when it’s exerting the former it demonstrates a remarkable ability to seem like it’s wallowing in the latter. No wonder so many developers – independent and otherwise – look to Super Metroid for inspiration. This is one of those rare games that you can look at and say, “Yes, this is how it’s done.”

– End: The Anatomy of Super Metroid –

“In a sign of class, the Metroid folks acknowledged Shine Spark exploits in Metroid Fusion, locking down certain potential sequence breaks but at the same time acknowledging the skill required to pull it off.”

While it’s nice that Metroid Fusion acknowledged it, I can’t say I’m cool with having to pull off pixel perfect YouTube speed runner maneuvers to collect standard item count upgrades. Metroid: Zero Mission is even worse about it; Bird Monster God help any crazy bastards who want to get 100% item completion and a good completion time in that game. I’d be more likely to try a minimalist run in MZM ‘cuz the sequence breaks for that aren’t as hard to do as getting more super missiles or power bombs.

Super Metroid, though, I could see myself getting a good time and all the items, even though the items aren’t necessary for endings in that one. Since it barely calls attention to the shine spark’s special functions (aside from the green emu thing’s lesson and that one missile upgrade in the vertical shaft in Maridia that requires upward flight), you know you’ve got what it takes to collect everything if you set your mind to it.

The Speed Booster puzzles in Zero Mission aren’t as hard as you think. The item I had the hardest time getting was that last Energy Tank where you had to Space Jump between all the lasers.

In general, the GBA games overly convoluted the whole idea of “puzzles” to snag minor pick-ups, trading immersion for ROM-hacky mousetraps that remind you you’re in a video game made of blocks.

In particular, the Speed Booster and Shine Spark were made much slower than in Super Metroid just to make their “puzzles” manageable. No longer do you get that out-of-control exhilaration of shooting across an area nearly faster than you can see.

Yeah, I’d agree that they aren’t all that hard, but they’re certainly a lot more elaborate. Honestly, that’s what I find so darn interesting about M:ZM. It’s like the designers looked at the ways people exploited Super Metroid and used that as a starting point.

It feels like M:ZM’s layout is a broken version of the game superimposed upon the the more expectedly paced level design, in addition to making the game for those players who’d rip it apart. They even have those secrets which let you get through end-game areas without the expected items, to enable those low-percent runs you mentioned. I know I’m not articulating it well, but I can’t think of any other 2D game that’s designed with that philosophy, or at least, not to that degree. That’s why I think M:ZM is seriously one of the strangest games out there.

But yeah, cool stuff.

To me, removing the double jump in Prime is just the supreme example of missing the point.

Whoops, that wasn’t meant to be a reply, but okay, sure, I’ll reply. Yeah, the micro-puzzle / ROM Hack situation in the GBA Metroids is such a pain in the butt I never want to 100% either game again, or even go near that number. But the real problem? The real problem is how if you save during Fusion’s endgame, you only get one short music track for the rest of your 100% item hunt!

I agree that some of the more “advanced” puzzles in Zero Mission are kind of infuriating due to the precision required to pull them off even once you’ve figured out what you’re supposed to do. In a lot of games that would bother me, but I guess the mechanics themselves are just good enough that I still had fun 100%ing it, even if I did have to bang my head against a few of them a few too many times in a row to get it down.

“If you’re really good, though, you can fly at a 45-degree angle – this requires exquisite timing …” It’s been a while, but I thought it was just a question of holding a shoulder button when you hit jump?

Yeah, that’s how I always did it.

Something else I never see anyone mention: Super Metroid has four different attract modes! The first is present from the start and shows Samus exploring Crateria “in character,” hesitating dramatically and pointing her gun arm at every suspicious crevice; after that, there are some basic tutorial clips showing how to open a red door, the “charge attack,” and so on. The second and third demos have hints for further in, like how the statue room works and where to find the Dachora. The final demo only unlocks after you beat the game and shows off the really crazy stuff, including the horizontal Shine Spark, special Power Bomb/Charge Beam attacks, and Crystal Flash.

This is yet another way Super Metroid teaches the player organically. You’re left to guess the exact means of pulling off some of these tricks, but as obscure as they are, the game shows them right to you—no strategy guide needed.

I didn’t know the last was only post-game. Gotta disagree on the Crystal Flash, though- I still have to look up how to do it. Funny enough, I originally thought it was just something made up for the Nintendo Power comic- along with Houston and all that other fun.

This is a fantastic series! I’m glad we have a writer as skilled as you to clearly map out exactly what makes Super Metroid so great.

Thanks, once again, Jeremy!

Congrats on finishing the Anatomy of Super Metroid! It’s been fun reading about this game that I haven’t played in many years, and yet still fondly remember. I’ll have to go back and play through it again now (if I can pull myself away from Diablo 3, that is).

I look forward to whichever game you chose go dissect next. My vote is for A Link to the Past!