Metroid revolutionized action games. Metroid II proved that you could make a satisfying and substantial sequel to a console game within the bounds of a portable system. And Metroid III — Super Metroid — advanced the state of the video game art considerably, relaying both an engaging story and the workings of a complex, non-linear platform shooter with barely a word. The third entry in the series was so good that many people declared it the greatest game of all time, period. And then… Metroid skipped a console generation, foregoing the N64 and Game Boy Color altogether.

Metroid Fusion, the fourth game in the series, wouldn’t arrive until 2002, more than eight years after Super Metroid‘s debut. Needless to say, it arrived with grand expectation in tow; sure, Nintendo was also publishing Metroid Prime on the same day, but that was a first-person shooter made by a bunch of Texans. This was the real Metroid sequel; not only was it directed by one of the key creators of Metroid and Super Metroid, Yoshio Sakamoto, the title screen even said Metroid 4!

Within a few days of Fusion’s release, however, many fans had unilaterally declared Fusion a disgrace to the Metroid name and Prime the true successor to the torch, interquel status and shifted genre designation notwithstanding. Fusion was deeply reviled for its linearity, its lack of atmosphere, and its constant dialogue and restrictions. Also, for Samus’ weird new blue suit.

But was Metroid Fusion really the garbage many disgruntled fans would have you believe? Yes, it’s very different in many ways than Super Metroid, but in hindsight these changes seem neither haphazard nor spurious. Nintendo deliberately set out to create a very different game than Super Metroid here, leaving the slavishly faithful approach to design to Retro with Prime — which is not a criticism of Prime. Retro took Metroid into the third dimension by following the Ocarina of Time template, carefully reproducing a 16-bit masterpiece not from laziness but rather to guarantee a rock-solid basis for a radical shift in play mechanics and possibilities. Prime is a 3D carbon copy of Super Metroid in many ways, and that superior foundation made for a brilliant work that excelled in its own right. It was a smart and effective approach.

But with Super Metroid being copied so meticulously by Prime, the team at Nintendo R&D1 needed to do something other than churn out a second direct reiteration of the Super NES classic. Their solution, not uncontroversially, was to create in Fusion a game that was in many ways the inverse of Super Metroid. It holds true to almost all of the fundamental tenets of Metroid, but it presents them in a different fashion in an unusual context.

In breaking down the design of Metroid Fusion, I’m not simply going to look at how the game reveals itself; I’m also going to demonstrate how Fusion is a worthy successor to Super Metroid by knowing when to mimic its predecessor and when to throw out player expectations. This won’t be an uncritical analysis, though. Fusion has flaws, and it has subjective failings that don’t appeal to all players. But on the balance, Fusion is a smartly designed game that plays with the rules of the series in order to prevent coming off as a tired rehash.

Eight years is a long time in video games, and the span between 1994 and 2002 proved to be particularly tumultuous. Games went 3D, gaining a new dimension; and with that new dimension, they developed a new vocabulary and a new way of communicating with players. Characters and narrative grew more important; abstraction began to fall out of fashion; and the find-your-own-way approach of Super Metroid gave way to tutorials and mechanical exposition.

Metroid Fusion came into a world that had little patience for its predecessor’s style. Super Metroid expected observation and patience and mental synthesis of its players; it offered copious clues, and its design nudged players in the proper direction, but it was rarely explicit about directions or even expectations. Masterful as Super Metroid‘s design was, its subtlety was no match for a new generation of gamers who preferred telling to showing, explanation to experimentation. Fusion had to be different — and, as Sakamoto has explained, the team wanted it to be different. Nintendo R&D1 was always about playing around with new ideas, and they’d already made the best possible Super Metroid imaginable with Super Metroid. The sequel needed to be something separate.

So even before the game begins, it throws you off guard by nearly killing Samus Aran.

For three games, the implacable, unstoppable, genocidal bounty hunter Samus Aran had taken the central role in Metroid adventures. Wordlessly, she defeated no end of creatures, always finding a much-needed tool to advance further and destroy new and more dangerous threats in the nick of time. At the end of Super Metroid, she basically functioned as death incarnate, supercharged with a metroid-powered energy beam capable to tearing through any enemy in a single blast.

So Metroid Fusion begins by tearing her down again to the weakest state the games had ever depicted her in. Metroid Prime did something similar, but it half-assed the idea, damaging Samus’ systems at the end of a prologue sequence but by no means stripping her of all her capabilities. Not Fusion, though. It commits cheerfully to the concept of Samus being disempowered and makes it the entire premise of the entire adventure.

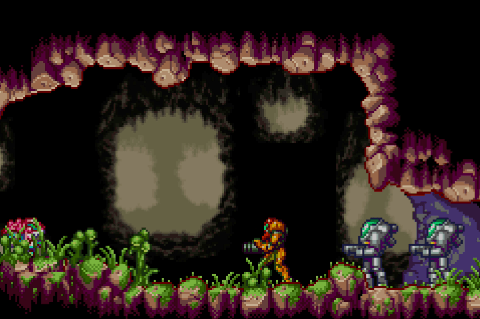

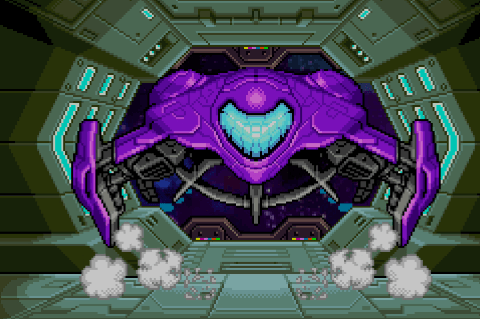

At the same time, it also develops the concept of who Samus is. Through prose and pantomime, Fusion‘s prologue depicts Samus’ fall from power, but it also shows hints of the larger world of Metroid. The title screen animation begins with Samus’ distinctive fighter craft flying alongside a frigate before crashing into an asteroid field; shortly after, a cut scene shows her leading a team of soldiers, driving home the idea that she really is the toughest and most capable bounty hunter around: She gets hired to take charge of the dirty work.

But that vanguard position also renders her vulnerable here, as a parasite set loose by her killing of a hostile creature on SR388 latches on to Samus and nearly destroys her.

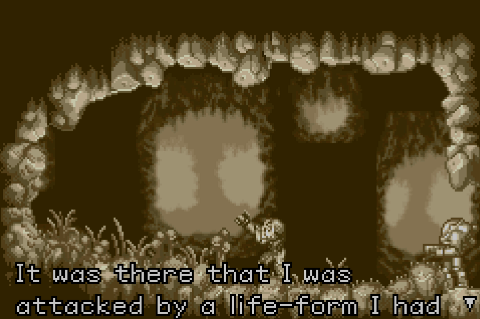

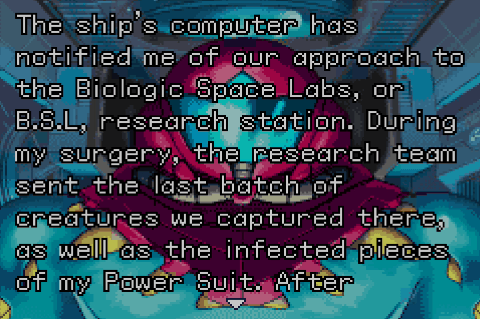

Fusion‘s introductory cutscene plays out as a sort of twisted parallel to Super Metroid’s introduction: Samus narrates as white-clad technicians perform operations.

But in this instance, it’s not a baby metroid being put under the microscope but instead Samus, who lies at the brink of death after her parasitic encounter. Rather than playing the role of outside observer, Samus has instead become the subject herself.

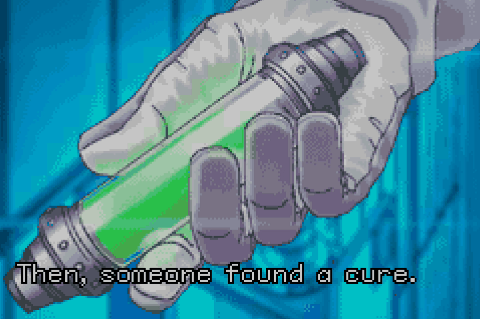

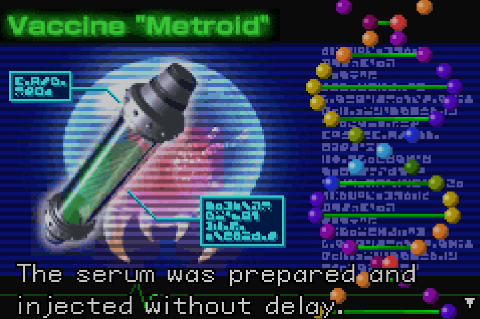

And here, as in Super Metroid, the baby metroid’s advanced capabilities come into play as the lab workers discover the creature’s curative properties: It alone can push back the infection that threatens to end Samus’ life.

The infusion of metroid DNA into Samus marks the big conceptual change behind Fusion’s story and play mechanics: Samus becomes part-metroid herself. The creatures that have existed as the central threat and motivating device for the duration of the Metroid series may be extinct, but their legacy lives on in the form of the woman who destroyed them.

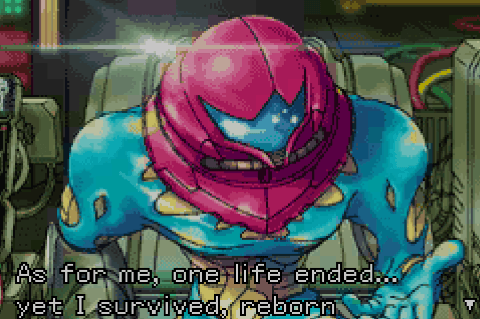

The metroid-infused Samus is fundamentally the same character, but she plays differently. She shares the same weaknesses as metroids — ice will freeze her solid — and she’s fundamentally weaker. Her attacks don’t hit as hard, she can’t juggle multiple powers, and she suffers far more damage from enemy attacks than in previous games. Even her profile changes, losing the bulky Power Suit/Varia components that defined her silhouette an adopting a slimmer profile reminiscent of her look in the original Metroid. More than that, Samus’ posture changes, with a ragged hunch to her stance that suggests weariness and fatigue.

The game goes to great lengths to convey Samus’ newfound vulnerability, in both subtle and dramatic ways. Most famously, Samus effectively becomes her own worst enemy; but her weakness is presented in other ways as well, some less obvious than the deadly SA-X.

Some of this is conveyed through game design, but much of it comes across in dialogue and monologues — quite different from Super Metroid‘s laconic approach. Still, they’re from different eras of game design, and Metroid Fusion does a lot with its dialogue to reinforce story and game concepts.

I’ve been looking forward to this one beyond any other game. It’s a very interesting Metroid experience and I look forward to reading the rest.

Excellent! I agree Metroid Fusion, while problematic in some ways, is often given short shrift by fans of the series. There’s still a lot of value in it.

Something the wording of your write-up just made me think of: Samus is vulnerable to the X-parasite in the prologue there, and the scientists save her by injecting her with Metroid DNA… but shouldn’t Samus, after the events of Super Metroid’s finale, *already* be infused with a bit of M-juice? Enough to make her weaponry lethal to X parasites? Of course you can come up with all sorts of justifications (the Hyper boost wore off after a while, Samus disabled the upgrade because it was unstable, etc), but it’s still kinda funny.

Also, did the last few FFVI Anatomy posts disappear?

Oh, good catch. Minor glitch on the last FFVI post, but all is well now. Thanks!

My impression of the Super Metroid finale was that the Baby Metroid was mostly providing an abundance of energy for her power suit and other equipment. I don’t think that would have altered her DNA.

“A wizard did it.” Problem solved!

Not just a wizard, but a SPACE wizard!

… which is, come to think of it, more or less what the Chozo are, right?

Uh oh, it’s finally happened. An anatomy on a game I’ve been meaning to play for ages but have never gotten around to. Do I keep up and risk spoilers? Hmmmmmm…

Play it on Virtual Console! It’s 8 bux. And a pretty brief game — maybe 5 hours or so.

I actually have a copy of the GBA cart around here somewhere, I just need to dig out the ol’ DS Lite (and its charger) (and then decide whether to play it tiny or stretchy I guess).

Oh hell yes! I have a soft spot for Metroid Fusion since it was the first Metroid game I played through and beat on my own. I agree that it doesn’t get enough respect (though I’ll freely admit there are problems with it)

Heck yes! I love Metroid 4. It’s a different beast than the rest of the series, but it’s an excellent game. I love the spritework & enemy design.

Ooo, this is exciting. I’ll be paying close attention to this one. I like some of the things Fusion does, but there were a few elements that turned me off, too. It will be interesting to revisit it with critical eyes.

Metroid Fusion is a personal close-to-favourite, if that makes any sense. I feel the only true failing it has is its damnable refusal to change the DAMN MUSIC if you’ve gone past the next-to-last cutscene. Trying to get 100% on a 30 second loop that refuses to go away no matter where yo go in the complex. I can’t believe that slipped past testing.

Fantastic write-up as always. I would have liked to see a little more analysis of more ways in which it differs from Super Metroid, but I suppose Samus being weak is the most significant and you hit the nail on the head with one.

Thanks. You do realize this is part one out of probably a dozen or more, right?

I remember specifically buying this game instead of Prime because I wanted to play an ‘old’ style Metroid game instead of ‘what they turned it into’. Like you said, it’s an entirely different experience than Super Metroid, but I loved it anyway. Hindsight is 20-20 right?

I can understand the design choices, but not necessarily agree with the actual implementation. Zero Mission is actually a fine example of this. Its more narrative focused, while not being that hand holding. And the adam revelation was so lame.

Anyway, one of the things I feel Fusion did right was the enemy AI. Having recently played most of the classic metroid games on sequence, its nice that the enemy patterns by metroid 3 got a few subversions here and there. The first bouncer type enemies you find vary from its m3 counterparts by throwing spines so you cant just shoot at it while it tries to engage you closer - you now need to rely on jumping to stay safe even at a distance. There are far more bosses with much different pattern variety. While the subversions are more gamey, they make combat a bit more interesting and engaging.

I kinda wish they didnt explain that most of the Federation enabled abilities were just data for samus to download. It doesnt make sense super missiles are data, unless somehow samus body manufactures them.

And I like how they cleaned up a bit the controls, since they had less input options. I dislike the more bombastic sound effects tho, but I guess it was a necessity given the handheld nature having to consider outdoors noise.

One quick thing is that I really loved how the SA-X moments really inspired moments of dread. It’s been a rare moment in all of my years of playing video games that I had moments of genuinely feeling helpless in a way that was a result of good game design. After you realized you couldn’t beat the SA-X, each of those moments created more urgency than any artifically manufacted timer.

Fusion may have been wordy at times, but the SA-X moments really felt like a perfect take on Super Metroids “Show, don’t tell” mantra.

Ah, yes. I think the SA-X moments are the hightlight of the game. Kinda wished there were more chase sequences whee you had to rely on trapping the SA-X, or maybe stealth sabotage it from progressing further. Since the game states that there were actually multiple SA-X, i would have loved a culmination of an encounter with more than one at a time.

Can’t wait to read more of this; I’ve played it, but got stuck at an SA-X segment partway in. Other stuff came up, so I never quite got back to it.

I was just talking about what a great game this was the other day. Very excited to read this series.